A calling for Howard Muscott, ’77, distinguished alumnus, came to him one day while looking in the mirror. Muscott was 13 years old, living with his single mother, sister, and grandmother in New York City. Until this seminal moment, Muscott felt self-pity that his father was not a part of his life, that he was different from the other boys he knew.

But on this particular day, Muscott looked at himself and said, “You have no reason to feel sorry for yourself. You can see. You can hear. You can walk. You can think.”

That revelation, coupled with the fact that Muscott had befriended a boy with a disability in his apartment building, sealed his career decision. He wanted to become an educator of children with special needs. And that he did.

For more than 30 years, Muscott has devoted his career to helping children with emotional, cognitive, and behavioral challenges as a teacher, consultant, principal, and college professor.

After earning a bachelor’s degree from Buffalo State, Muscott earned two master’s degrees: one in education and human development/early childhood education from George Washington University, another in instructional practices in special education from Teachers College, Columbia University, where he also earned a doctorate in special education/emotional disturbance.

In 2002, he founded the New Hampshire Center for Effective Behavioral Interventions and Support, a center for professional development and research he now directs. The center has worked with hundreds of teachers and administrators throughout New Hampshire and beyond to promote positive and preventative school discipline systems, and in doing so, improve the emotional well-being of all children.

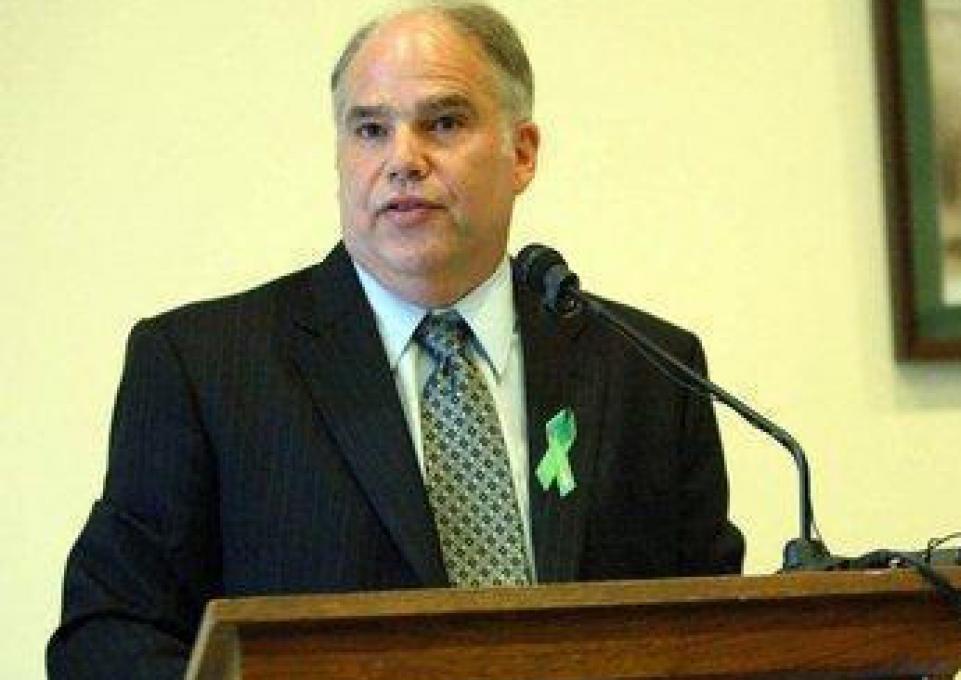

Muscott, who visited the Buffalo State campus in late November to deliver the keynote address during the Dr. Horace “Hank” Mann Graduate Research Symposium, explained that the impetus for the center stemmed from concerns, such as “disruptions in class, unsafe school climates, bullying, tardiness, absenteeism, and to some extent, physical aggression.

Muscott, who visited the Buffalo State campus in late November to deliver the keynote address during the Dr. Horace “Hank” Mann Graduate Research Symposium, explained that the impetus for the center stemmed from concerns, such as “disruptions in class, unsafe school climates, bullying, tardiness, absenteeism, and to some extent, physical aggression.

“The question was: ‘How do we turn this around without an overreliance on the use of punishment?’ Our effort was to be way more expansive than that.”

Using a multi-tiered system of behavior support, Muscott and his staff focus on what schools can do to help all children learn better, how to respond to students at risk, and finally, what they can do to help the small percentage of students with chronic and intensive behavior problems.

Under his leadership, 30 percent of public schools and the majority of Head Start programs in New Hampshire have implemented these interventions and support over the past 12 years. Additional schools in Alaska, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Vermont also have tapped into Muscott’s expertise. The result, he said, has been reductions in problem behavior, office discipline referrals, suspensions, and dropouts and increases in positive social behavior and school climates.

Muscott points to the Buffalo State faculty who laid the foundation for the principles he has put into effect throughout his career.

“They instilled in me the ideas of professional rigor, personal responsibility, and reflection,” he said. “I always come back to that.”

Muscott’s philosophy is that all children can learn and develop socially and emotionally.

“We believe in not giving up on any student, regardless of need, regardless of past experience,” he said.