Location, location, location. It’s a primary factor driving the value of homes, especially as interest grows for urban living and what planners call “walkability.” According to Jason Knight, assistant professor of Geography and Planning and coordinator of the urban and regional planning program, planners see walkability as an asset that makes neighborhoods more desirable places to live.

Knight is the lead author of the article “Walkable and resurgent for whom? The uneven geographies of walkability in Buffalo, NY” published in Applied Geography in March 2018.

“I’m interested in understanding cities from the neighborhood perspective,” Knight said. “We tend to talk about cities as one monolithic thing. As a practitioner and academic, I’m interested in why neighborhoods vary and how policies affect them.”

Knight describes Buffalo as a “shrinking city”—a city built to accommodate a population of nearly 600,000 that now houses less than half that. “The planning profession,” he said, “focuses a lot on managing growth, not decline. But policies focusing on growth don’t improve distressed neighborhoods when growth is unlikely in the short term.”

Knight describes Buffalo as a “shrinking city”—a city built to accommodate a population of nearly 600,000 that now houses less than half that. “The planning profession,” he said, “focuses a lot on managing growth, not decline. But policies focusing on growth don’t improve distressed neighborhoods when growth is unlikely in the short term.”

Whether growing or shrinking, cities have both highly desirable neighborhoods and those that attract few new residents. “I’m most interested in distressed neighborhoods,” said Knight. His reason is simple: People live there. “We can’t assume investments outside these neighborhoods will trickle down to them,” he said.

He believes that current policy in Buffalo continues the national trend of applying market-driven, public-private solutions. “When people talk about Buffalo’s so-called resurgence, they’re focusing on places like the Medical Campus, Canalside, or Solar City,” he said. “But I think the resurgence narrative should be challenged because we haven’t solved the problems of concentrated poverty, segregation, and disinvestment in distressed neighborhoods.”

A critical challenge for residents in these distressed neighborhoods, where low automobile ownership is the norm, is access to day-to-day needs, according to Knight and his coauthors.

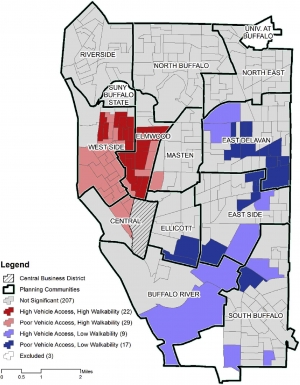

The authors spatially analyzed walkability across Buffalo’s neighborhoods using data from the U.S. Census and WalkScore.com. They found the most walkable areas in Buffalo tend to be clustered in stable neighborhoods and those undergoing reinvestment. On the other hand, neighborhoods with lower WalkScores tend to be distressed with high vacancy rates, high numbers of vacant lots, and limited reinvestment.

When analyzed with auto ownership data, they found neighborhoods such as the Elmwood Village have high walkability and high auto ownership, meaning walking is a luxury rather than a necessity. On the East Side, low auto ownership rates and lower walkability leave residents disconnected from daily needs.

The West Side neighborhood is especially interesting because—unlike the East Side—it is highly walkable while also having lower rates of auto ownership. Residents can rely on walkable access to daily needs. However, as the West Side sees increasing reinvestment and increased sale prices and rents, it’s questionable if its current residents will be able to afford to remain there.

What this means, Knight suggests, is that the desirable trait of walkable neighborhoods—a hallmark of shrinking cities built before automobiles appeared—is at risk of becoming a trait only available to the affluent. He suggests government policy should not be linked exclusively to market-driven solutions but also to public policies that are community-based, equitable, and inclusive. “There is no single answer,” he said. “But community activism and policy that invests in human capital are good first steps.”