Tired of the dark, seemingly shorter days? You’re in luck. Starting December 22, the amount of sunlight in a day starts to creep back up.

But what happens on December 21, the first day of winter?

That’s the winter solstice, the day of the year with the least amount of sunlight in the Northern Hemisphere. And while the winter solstice signifies the beginning of the end of the long, dark days of winter, it has had deeper significance for thousands of years, in many different cultures.

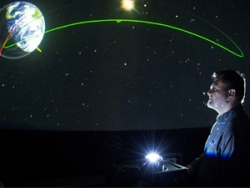

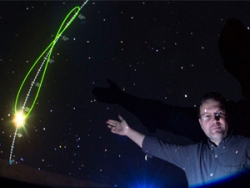

“People were always observing the motions of the sun and the stars and things like that,” said Kevin Williams, director of Buffalo State's Whitworth Ferguson Planetarium and associate professor of earth sciences and science education (pictured).

“Stonehenge is an example of a monument or structure that lines up with the sunset on the winter solstice,” he said. “There are other monuments or structures like that, that line up with the sun rising and setting on different days of the year.”

It’s unclear why Stonehenge was constructed, Williams said. It may have been built as a ceremonial or religious structure, or as a calendar of sorts. The Drombeg megaliths in Ireland and Rujm el-Hiri in northern Israel are two structures that similarly align with solar benchmarks.

It’s unclear why Stonehenge was constructed, Williams said. It may have been built as a ceremonial or religious structure, or as a calendar of sorts. The Drombeg megaliths in Ireland and Rujm el-Hiri in northern Israel are two structures that similarly align with solar benchmarks.

The winter solstice has also been a reason to celebrate over the centuries, more so than the summer solstice, Williams said. That’s because the winter solstice marks a turning point, when the sun is lowest in the sky, meaning the days afterward would start seeing more sunlight again. In other words, we've survived our darkest days. In some cultures, it was also a time to slaughter their livestock, as opposed to providing for the animals during the winter months.

“Even though it’s the Nothern Hemisphere’s first day of winter, it’s not the coldest time of year,” Williams said, referring to the solstice. “It gets colder after that. But it was kind of a marker for them.”

From a scientific standpoint, the reason for the winter solstice has to do with the earth’s axis and how the planet orbits the sun. In the Northern Hemisphere, leading up to and during the winter, we’re facing away from the sun, Williams said. That’s why the sun is lower in the sky, and why we get less direct sunlight.

“The winter solstice is the point in the Earth’s orbit when the pole of the Earth's axis is at its farthest away from the sun,” he said. “After our winter solstice, the north pole of Earth's axis is tilted less and less away from the sun as Earth continues on its orbit.”

While the ancients used to celebrate the winter solstice, there are other impacts from the darkness that descends over the Northern Hemisphere for several months of the year.

“When you think about it, our lives are really affected by how high in the sky the sun is and how that changes over the course of the year,” Williams said. “In terms of people’s personalities or attitudes with longer nights in the wintertime. People throughout time have been greatly affected by the change of the sun’s angle in the sky.”

During the short, dark days of winter, people can suffer from things like seasonal affective disorder. We tend to eat more, feel sleepier, and lack motivation for things like exercise. Traditionally, the winter solstice helped people with the timing of the harvest, preparing the fields, and as mentioned, slaughtering the livestock.

After the winter solstice, we gain between 90 seconds and two minutes of daylight through January each day. In February, we gain about two and a half minutes of sunlight each day. That cycle continues through the vernal equinox in March, when the length of day and night are nearly equal. In June, the longest day of the year is marked by the summer solstice, after which the amount of daylight starts to decrease again, through the autumnal equinox and, eventually, the winter solstice.

The winter solstice doesn’t always fall on December 21, Williams said. It depends on factors like the leap year, and where you are in the world.

“It’s an astronomical thing, as far as where Earth is at a specific time,” he said. For instance, the solstice will occur at 11:19 p.m. on December 21 for those of us in Buffalo. “For people east of here, like say in Europe, it’s going to be on the 22nd, because they’ve already passed midnight,” he said. “It’s a specific point in the earth’s orbit, and that’s why it’s recorded as a specific time.”

If the idea of more sunlight puts you in a celebratory mood, you can do as the ancients did, and throw a party Saturday to celebrate. After all, the vernal equinox will be here before you know it.

Pictured: Kevin Williams, associate professor of earth sciences and science education.

Photos by Bruce Fox, campus photographer.