When she was a little girl, Susan Daniel wanted to be a benthic taxonomist, although she didn’t put it quite like that.

“I was always fascinated by the little creatures that lived in the creek that runs behind our house,” said Daniel, who grew up on a dairy farm in Ohio. “I wanted to know more about them. I really like creepy crawlies, and worms are my favorite critters to try to identify.”

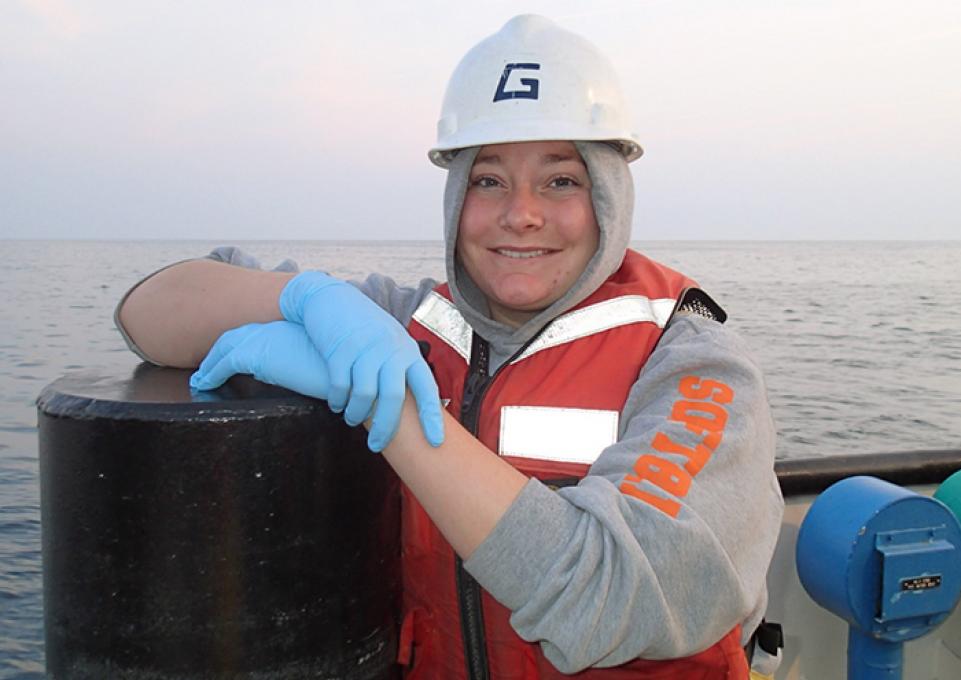

Benthic invertebrates—small animals including worms that live at the bottom of water bodies—are Daniel’s specialty. She is senior research support specialist at the Great Lakes Center, a position she started in May 2013. Her responsibilities include traveling with the R/V Lake Guardian, the EPA ship that monitors the water quality in the Great Lakes, as the senior benthic taxonomist. Every year, scientists take samples of the benthic organisms using equipment that grabs material from the bottom of the lakes.

“We put the samples in jars and label them,” said Daniel, “and we bring the benthic samples here for identification in our lab.” The work is funded by a $1.1 million grant to the Great Lakes Center via subcontract from Cornell University, which received a $3.9 million grant from the EPA Great Lakes National Program Office for Great Lakes Long-Term Biological Monitoring.

“Those organisms can show a whole picture of the year-round condition of the lakes,” said Daniel. “Some benthic organisms tolerate pollution better than others. So when we know what's living there, we can determine if the water is polluted, not polluted, or somewhere in between. We are looking at profundal zones—really deep water—so if we see a change in the organisms, we know something is having a pretty big impact on the ecosystem.” That’s where the ability to identify organisms becomes significant—and that’s part of what a taxonomist does.

“This is my fourth year going out on the Guardian,” said Daniel. “I’ve been on all the Great Lakes. Every year, we start on Lake Michigan, and then travel to Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario before going to Lake Superior. The whole cruise takes about four weeks.”

Daniel, a graduate student in the Great Lakes Ecosystem Science master’s program, graduated from Heidelberg University in Ohio with a major in environmental science and minors in biology and chemistry. She was working in Heidelberg’s National Center for Water Quality Research lab when her supervisor recommended her for a position at the Great Lakes Center. She started working four days after graduating.

Daniel was nominated as a United States student member of the board of the International Association for Great Lakes Research and subsequently elected to the board. Her two-year term begins in June 2016.

“Everything I’m doing came from trying to learn more about the tiny animals living in that little creek on the farm,” Daniel said. “There is so much we don’t know about the creatures living in Earth’s waters.”