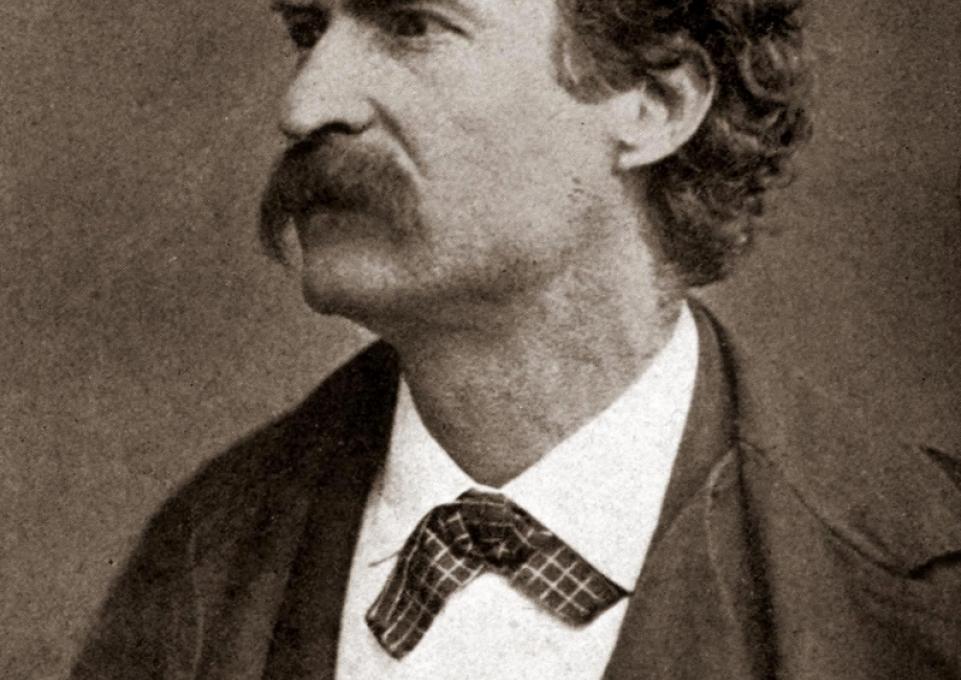

Mark Twain came to Buffalo 150 years ago with dreams of advancing his newspaper career. And while he spent just 18 months in the Queen City, the prolific author and humorist left an indelible mark on the city.

In honor of Twain’s contributions to Buffalo, Mayor Byron Brown, ’83, will proclaim August 14, 2019, “Mark Twain in Buffalo Day” during a formal ceremony at noon at the Central Library, 1 Lafayette Square, in downtown Buffalo. The celebration will feature an illustrated lecture by Thomas Reigstad, professor emeritus of English and author of Scribblin’ for a Livin’, a book about Twain’s time in Buffalo. The library will also announce its recent digitization of the original manuscript of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which is housed at the Central Library.

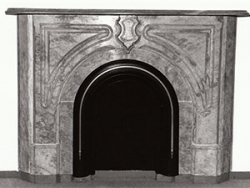

Twain’s connections to Buffalo State College are twofold: a fireplace mantelpiece rescued from his mansion at 472 Delaware Avenue (now demolished) adorns the wall of the Butler Room in E. H. Butler Library; and Buffalo State houses the library archives of the Courier-Express, the paper whose forerunner Twain came to Buffalo to work for, as managing editor and one-third owner, arriving in the city on August 14, 1869.

The story of how the mantel ended up at Buffalo State starts with Richard Thurston, a New York Telephone company employee whose territory included Twain’s Delaware Avenue neighborhood. When the Twain home was being demolished after a fire in 1963, Thurston asked if he could take a few bricks, as he was building a fireplace in his own home. Then he spotted the mantelpiece and asked for that, too.

The demolition company foreman wanted $20, and Thurston gladly hauled it away. The mantelpiece was coated in brown paint, but Thurston quickly realized it was solid marble. He gave the Victorian-era antique—the only one of the home’s many fireplaces not damaged in the fire—to a friend, D. Paul Smay. Smay was a professor of art education at Buffalo State from 1946 to 1956 and an avid collector of antiques. A Pennsylvania native, Smay moved on to become dean of academic affairs at Shippensburg State College, and he had planned to donate the mantelpiece to his new school’s rare book room. But Paul G. Bulger, then president of Buffalo State, convinced Smay that the mantel should stay in Buffalo, according to a 1967 article in the Buffalo Evening News. Smay agreed, and he donated the fireplace—now stripped of its paint and polished to a rich luster—to Buffalo State on April 25, 1967.

Most of the rooms in Twain’s Delaware mansion had either ornately carved wooden mantelpieces or marble mantelpieces with custom-designed keystones in the shapes of palm leaves, date clusters, bison heads, or elaborate floral patterns, Reigstad said. Buffalo State’s marble mantelpiece, which came from the downstairs dining room, has a simple cast iron ring and a stately shield as its keystone. It was likely manufactured across the street by the C. S. Cooper Marble Works, at 511 Delaware.

Most of the rooms in Twain’s Delaware mansion had either ornately carved wooden mantelpieces or marble mantelpieces with custom-designed keystones in the shapes of palm leaves, date clusters, bison heads, or elaborate floral patterns, Reigstad said. Buffalo State’s marble mantelpiece, which came from the downstairs dining room, has a simple cast iron ring and a stately shield as its keystone. It was likely manufactured across the street by the C. S. Cooper Marble Works, at 511 Delaware.

For decades the fireplace was mounted on a wall in the conference room of Butler Library’s director. This summer, it was painstakingly disassembled and re-installed upstairs in the Butler Room.

The story of how the Courier-Express library archives wound up at Buffalo State is equally fortuitous. Like the mantelpiece, the Courier archives could have gone to another university, but they didn’t.

The Courier-Express was formed in 1926, when the Buffalo Morning Express merged with the Buffalo Daily Courier. It occupied the building at 795 Main Street, now home to the Catholic Diocese of Buffalo, publishing daily until September 19, 1982, when it printed its final edition.

Several institutions of higher learning were interested in obtaining the paper’s archives, including Buffalo State College, Syracuse University, and Cleveland State University. Reigstad, who worked as a copy editor at the Courier-Express until it closed, was also an assistant professor of English at Buffalo State at the time. Part of a joint committee comprising representatives of the college and the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society (now the Buffalo History Museum), Reigstad was tasked with writing the formal proposal to the Cowles Media Company, the paper’s last owner.

Reigstad’s proposal prevailed, and the Courier’s library archives—from the late 1950s to the final edition—were donated to the Buffalo History Museum and Buffalo State, where they’re currently maintained in E. H. Butler Library’s Archives and Special Collections. The collection consists of the Courier-Express article morgue of 1 million newspaper clippings, over 100,000 photographs, the microfilm collection, furniture, newspaper racks, and assorted memorabilia.

Buffalo State archivist Daniel DiLandro noted the importance of the collection for students, staff, faculty, the Buffalo community, and other scholars.

“The Courier-Express is our most often-utilized collection,” DiLandro said, “attracting hundreds of scholars from around the world every year, sometimes supplementing research, and often serving as a platform for thesis and other student-centric work.”

DiLandro said the college recently partnered with the Buffalo History Museum to digitize the complete run of the Buffalo Express from the period of Twain’s editorship, from 1869 to 1871. The keyword-searchable database project was made possible through a grant from the Western New York Library Resources Council.

The library also houses the Twain Family Papers Collection (reproductions).

Back when Twain moved to Buffalo, the Courier-Express was the Buffalo Express, located on East Swan Street. On August 14, 1869, at the office of attorneys Rogers and Bowen on Erie Street, Twain signed the contract to become the paper’s co-owner and managing editor.

Soon afterward, Twain married Olivia Langdon, daughter of an Elmira-based coal magnate. A man of humble origins, Twain had planned to find an upscale boarding house for himself and his new bride, but his father-in-law had other ideas: Jervis Langdon purchased the home at 472 Delaware Avenue—with its many fireplaces—as a gift for the newlyweds.

Twain left Buffalo in March 1871, following a series of personal tragedies. His infant son, Langdon, born premature and on death’s door from birth, would live for just a year and a half. His wife, Olivia, was also gravely ill with typhoid fever. Twain had grown tired of the day-to-day journalism grind; he sold his share of the Buffalo Express, for a loss, and moved the family to his in-laws’ home in Elmira to convalesce.

Twain eventually went on to Hartford, Connecticut, and to further fame, writing such American classics as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. While he didn’t write the novels in Buffalo, the Queen City is where the ideas for them started brewing, Reigstad said.

“One snowy Sunday afternoon in February of 1870,” Reigstad said, “Twain sat in his library at 472 Delaware and, with his wife napping upstairs, wrote a letter to a childhood friend back in his hometown of Hannibal, Missouri. The letter unlocked a string of memories about old times growing up in Hannibal. Twain recalled town characters, mutual buddies, amusing and tragic incidents that years later formed the basis for themes and characters centered on the fictional Tom and Huck. The origin of what is known as ‘The Matter of Hannibal’ was hatched in Buffalo.”

Twain would return to Buffalo several times over the course of his life, visiting old friends and places. He owned property here, collecting rent and paying taxes on a waterfront slip at the foot of the Erie Basin Marina until his death in 1910. The city he called home for a year and a half would remain an indelible part of his life. And two pieces of Twain’s life in Buffalo remain an indelible part of the Buffalo State campus community.