In today’s world of junk mail, ubiquitous Post-Its, and throwaway party supplies, it’s hard to imagine that the average American once found paper hard to come by. But around 1800, paper—then made from rags, not wood—was expensive. So books were expensive, too.

“Not everybody owned books,” said Lisa Berglund, associate professor of English. “A middle-class family might own about five books, most likely including a Bible, a schoolbook, an almanac, a book of hymns or songs, and a dictionary.”

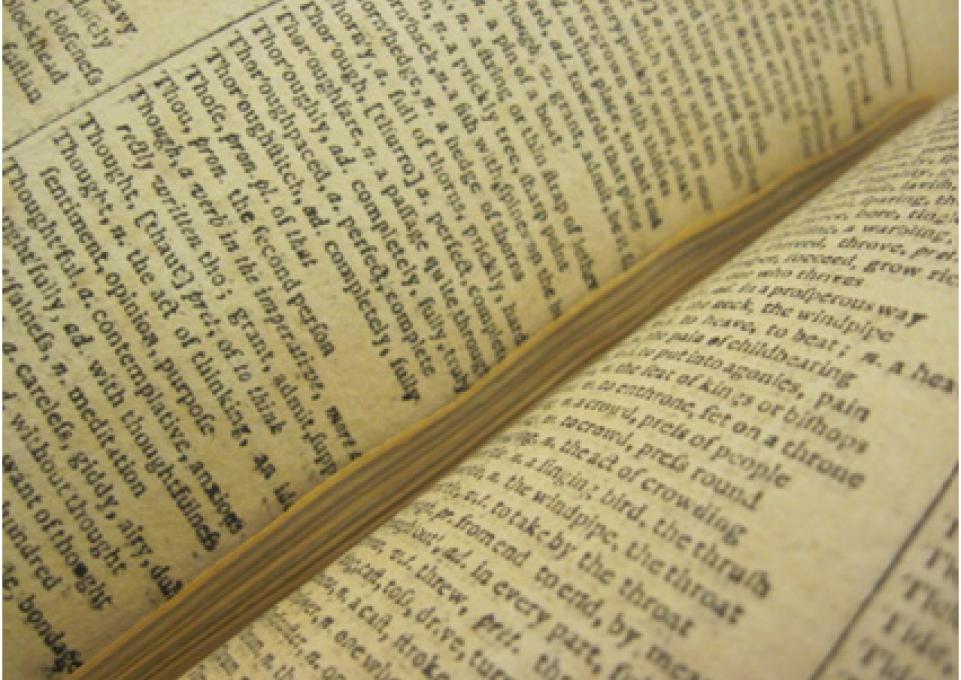

Those dictionaries have piqued Berglund’s curiosity. She is studying the annotations people made in their dictionaries, limiting her research to small-format dictionaries printed in the United States between 1785 and 1835.

To date, she has examined 224 individual dictionaries, scrutinizing each of them for any notes, marks, and drawings—something she has found in 96 percent of the dictionaries she has examined. “A dictionary is a space that permits a lot of different responses,” she said. “They have a kind of flexibility.” Most dictionary owners expected to keep the book for their lifetimes and to leave it to their families.

In an 1807 spelling dictionary (pictured left), “Miss Doretta Richards /And Mr. Wm. Thombs Esq/ justice of the peace” was written. Under it, one J. W. Thombs wrote: “This was written by Abraham Richards my mother’s brother just before her marriage to my father in 1818…he was then a boy This was my mothers school Spelling book when a girl, & I her only child, am tonight nearly 78 years old writing this note.” The entry is dated October 15, 1898.

In an 1807 spelling dictionary (pictured left), “Miss Doretta Richards /And Mr. Wm. Thombs Esq/ justice of the peace” was written. Under it, one J. W. Thombs wrote: “This was written by Abraham Richards my mother’s brother just before her marriage to my father in 1818…he was then a boy This was my mothers school Spelling book when a girl, & I her only child, am tonight nearly 78 years old writing this note.” The entry is dated October 15, 1898.

Such an inscription would fall under “a record of family history,” one of ten uses Berglund has identified for the dictionary. Another is “a valuable family possession,” and, to protect their dictionary, some owners employed book curses. For example, one dictionary bears the inscription “This Book is one thing/And hemp is another/Steel not the one for fear/of the other.”

“Sometimes the dictionaries were used by children as schoolbooks,” Berglund said, “although we can’t assume that awkward cursive writing was only the work of children. Adults struggling to learn to write may have used the dictionary to practice in, too.” Because of the scarcity of paper, dictionaries were places to practice handwriting, to sketch, and to keep records, such as, “I agreed with the Widow Clara Lawrence To board with her for one dollar & fifty cents per week…” Because people expected to keep the dictionary, it was logical to keep important records and cherished mementoes in it.

So far, Berglund has identified 10 ways people of that era used dictionaries: paper; a place to assert identity; a sketch book; a flower press and scrapbook; a valuable family possession; a record of family history; a diary or memorandum book; entertainment; and a commonplace book. And even, sometimes…a dictionary.