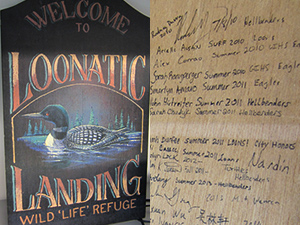

A large, mounted wall hanging of a common loon greets visitors to Amy McMillan’s lab in the Science and Mathematics Complex. The piece was a gift from one of the first undergraduate students she mentored after joining the Biology Department in 2003. Every year since, young scholars completing research under McMillan’s watchful guidance sign the back of the picture, which now boasts scores of signatures and is nearly full.

Since it was formally established in 2003, the college’s Undergraduate Research Office has guided thousands of Buffalo State students from all academic disciplines through projects ranging from research, scholarly, and creative activities integrated into individual courses, semester-long independent projects, and summer fellowships. While the duration may vary, these intensive examinations all involve meaningful student-mentor interaction.

This week, students from across the campus will present their preliminary and completed research, scholarly, and creative activities at the 18th annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration.

“The value of the relationship that develops between students and mentors cannot be underestimated and can lead to transformative changes in the student, although mentors also benefit greatly from these interactions,” said Jill Singer, director of the Undergraduate Research Office, professor of earth sciences and science education, and Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) Fellow.

Mentoring can develop lasting professional relationships that go beyond the research itself to bloom into full academic partnerships. Many alumni whose first research experience was completed as undergraduates have gone on to advanced degrees and, in some cases, returned to their alma mater to teach, mentor, and lead.

“When I was an undergrad at North Dakota State, I worked very closely with my mentor. He influenced me the most,” said McMillan, associate professor of biology. “I vowed that when I got a full-time job that was the kind of work I would do.”

McMillan didn’t have to wait long to fulfill that promise. One week after arriving at Buffalo State, an undergraduate walked into her office looking for guidance. In a twist, the student’s search for a mentor would completely alter the path of McMillan’s own research.

Together, Foster and McMillan have co-authored several articles on their findings, which have helped lead New York State and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider listing hellbenders as an endangered species.

Converging Paths

“In high school, I was one of those people who didn’t know what they wanted to do after graduation because I liked everything,” said Robin Foster, ’04, ’06. “I loved biology, I loved working with animals. But everyone told me, ‘There are no jobs in that.’ So I picked a different career.”

“In high school, I was one of those people who didn’t know what they wanted to do after graduation because I liked everything,” said Robin Foster, ’04, ’06. “I loved biology, I loved working with animals. But everyone told me, ‘There are no jobs in that.’ So I picked a different career.”

After earning a degree in education, Foster spent several years teaching at elementary schools. When an opportunity to return to college appeared, she jumped at the chance and decided to revisit her passion for wildlife conservation as a biology major. A professor suggested she contact the department’s then newly hired faculty member, McMillan, who had a background in zoology and ecology.

“Robin was the very first person through my door,” said McMillan with a smile. “I learned how to mentor by mentoring her. It turned out to be a super successful relationship.”

With McMillan’s encouragement, Foster applied for and was awarded an Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship in 2003. In her senior year, she studied the effects of mercury contamination on the Bald Eagle and the Belted Kingfisher population. The experience proved life-changing and Foster decided to pursue her master’s degree in biology at Buffalo State.

Meanwhile, McMillan had been reading about the plight of the hellbender, a large salamander found in New York State’s Susquehanna and Allegheny rivers, which had seen a rapid population decline since the 1980s. The hellbenders’ dwindling numbers were indicative of poor water quality in the region.

McMillan shared her discovery with Foster who immediately connected with the research possibilities and used it as the basis for her master’s thesis. Foster has continued her examination of hellbenders as a doctoral candidate at the University at Buffalo, as part of the New York State Hellbender Work Group and, recently, as a mentor to undergraduate students.

“Amy was about the best mentor I could have hoped for and she has been that to so many students,” said Foster, who is currently completing her Ph.D. in UB’s evolution, ecology, and behavior program. “We have discussed not just my own research, but also applying to grad school, being an early-career professor, and the tenure process. My work with Amy has offered me a really unique view of this career as a whole.”

McMillan cites Foster as an equal inspiration. “I only am doing hellbender research because of Robin. Because she said she was interested, it turned into 13 years of my career.”

The Process, Not the Product

One of the hurdles undergraduate mentors face is instilling confidence in their students. Many first-time researchers are naturally concerned about obtaining desirable outcomes, being thorough, and, simply, making mistakes.

One of the hurdles undergraduate mentors face is instilling confidence in their students. Many first-time researchers are naturally concerned about obtaining desirable outcomes, being thorough, and, simply, making mistakes.

On the first day of her eight-week Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship studying hellbenders in the Susquehanna watershed, senior biology major Megan Kocher felt she had already ruined her research project. Kocher, along with fellow biology majors Shelby Priester and Sonya Bayba, were establishing sampling points to collect data.

“We really screwed up a couple of things on that first day,” Kocher says with a slightly nervous laugh. “We lined up our transects incorrectly and some of our data got messed up. We decided we needed to tell Robin, but we all felt sick to our stomachs about it. We talked to her and she was very reassuring. She was really great about helping us fix everything. It was a rough first day!”

“When I saw how upset they were that day, I knew it meant we had a great crew,” said Foster. “It meant they really cared and it mattered to them that they do it correctly. That gave me a lot of confidence that they were going to be fast learners.”

After the short stumble of the first day’s field research, the student group faced a larger challenge—near constant rain.

“With all the rainfall, the streams would either be too high or too cloudy to get into,” said Kocher. “The sediment would get mixed up, so we couldn’t do anything until it cleared out.”

“With all the rainfall, the streams would either be too high or too cloudy to get into,” said Kocher. “The sediment would get mixed up, so we couldn’t do anything until it cleared out.”

“In mid-to-late June they contacted me and said ‘We need to talk,’” said McMillan. “I really thought there must be a serious problem. They said, ‘We can’t get our work done. What are we supposed to do?’ It was great, because I was able to say, ‘This is what happens. Don’t worry! No matter what, there are things we are going to get out of this.’”

Singer's reaction to hearing this story is to nod in agreement and repeat something she often tells students and mentors at the start of their research experiences: “Undergraduate research is more about the process than the product.”

“Of course, it is important to identify a desired outcome, but if the focus is only on results, students can get discouraged when things do not go according to their original plan,” added Singer. “The very nature of research is that answers are not known in advance and that more often than not, unanticipated challenges must be dealt with. But overcoming the challenges is what leads to greater confidence, problem-solving skills, and a powerful-learning experience.”

Unexpected Outcomes

While some undergraduate students fret about project outcomes, they may not realize one of the essential results of research until it has already happened—self-discovery.

While some undergraduate students fret about project outcomes, they may not realize one of the essential results of research until it has already happened—self-discovery.

Kocher, who is set to graduate in December, learned that while she loved her field research experience, she’s not suited to the hours of lab time required to analyze data. She’s considering her options after graduation, but already has a good idea of what she’d like to do.

“I’m leaning more toward something involving travel. Working at a national park, something less research-based and more to do with the outdoors and people.”

Alternately, Kocher’s research partner, Shelby Priester, has gained the confidence and expertise to consider research as a full-time path. Last summer’s project studying hellbenders was Priester’s first research experience—it clicked.

“First, I learned I was capable of doing field research, which I was terrified of,” said Priester. “I was worried if I didn’t like it that I’d have to change my whole career plan and major.”

Priester is currently applying for field-oriented summer research jobs all over the country. After she graduates in 2017, she plans to pursue a graduate degree in biology, zoology, or wildlife conservation.

“This experience made me realize that this is what I want to do. I want to get back out there and do what I did this past summer, but in a different setting with a different species. I want to learn new methods.”

Foster and McMillan revel in the transformations their students have made, but are not altogether surprised.

“I love both teaching and doing research,” said Foster, who hopes to find a position at a small university or college after earning her doctorate. “I feel that undergraduate research mentoring really is the piece that brings those two parts together.”

And so it has for countless Buffalo State students.

As Priester leaves her lab and prepares for another class, McMillan calls after her, reminding the student, “Don’t forget to sign the loon plaque!”

Photos

Top: Foster, McMillan, and Priester in the Conservation Genetics Lab

Second from top: Foster carefully holds a hellbender

Third from top: Kocher in the field for her Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship (July 2015)

Third from bottom: Field crew getting ready to set bait for a night survey. From left: Bayba, Kocher, Priester, and NYS DEC wildlife technician Seth Liddle.

Second from bottom: Kocher searches for hellbenders underwater

Bottom: The loon wall hanging signed by McMillan's former research students